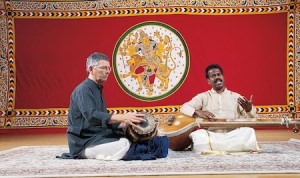

Michael Darer ’15 attends a concert presented by vocalist B. Balasubrahmaniyan, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Music; as well as David Nelson, Artist in Residence, and violinist L. Ramakrishnan.

One of the most frustrating things about seeing a great concert is how effortlessly the musicians seem to produce their sounds, while at the same time recognizing how complex and daunting the music truly is. As someone wholly ungifted with any sort of instrument (a deficiency for which I compensate with oppressive, too loudly aired opinions), this sort of dual recognition is especially apparent to me whenever I see truly gifted musicians perform. I find myself awed, annoyed and baffled at how incredibly deftly instrumentalists and vocalists produce their art in all its dumbfounding intricacy, while knowing that I would probably break whatever instrument they’re handling if I so much as attempted to play scales. However, there are some times, in the presence of brilliant music, when even this mental poltergeist is unable to sneak into my perception of a show. Sometimes, that seemingly incompatible ease and complexity meld together. My evening listening to B. Balasubrahmaniyan was such an occasion.

Balu, a vocalist specializing in South Indian music and an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Music at the University, was originally supposed to perform at the Navaratri Festival in mid-October but was, unfortunately, forced to postpone due to illness. It’s a shame he wasn’t able to sing as originally scheduled, for, as someone with little knowledge of Indian music, it would have been interesting to compare his style and material to other acts, but, on the whole, I’m simply glad I got to see him at all.

With Balu that night, was Artist in Residence David Nelson, playing the mridangam (a percussion instrument featured prominently in Carnatic music, which Nelson specializes in) and violinist, L. Ramakrishnan. Sitting in a semi-circle on the stage of Crowell, the three men proceeded to produce two hours of some of the most complex, astounding music that I’ve ever heard.

Before I gush, however, a quick background on Carnatic music:

Carnatic music, which is considered one of the two major types of classical Indian music, is associated mainly with the southern part of India. It is usually performed by three individuals, one of whom is the main performer, while another provides melodic accompaniment, and the third, rhythmic accompaniment. Carnatic music is organized around four main “principles”: relationships in pitch between notes (sruti), cycles of rhythm (tala), the individual note (swara), and the overall structure of the piece (raga). These components pop up both in improvisation and scripted performance and, together, form the essential musical backbone of the genre.

When considering these four ideas, it is hard not to notice the dual emphases on individual sounds and the way in which those sounds fit into the larger sonic landscape. When listening to Balu, though I was unaware at the time of the specifics of each aforementioned principle, this was abundantly clear. Each of the three musicians produced an individually magnificent thread of sound, from Nelson’s alternating, multi-faceted tempos, to the violin’s mournful swoops, to Balu’s dynamically wavering voice. Each portion of the whole displayed unprecedented musical eloquence and, on its own, each was magnificent. However, none were really the “focus” per se. Certainly, Balu was front and center, but even his singing never dominated the trajectory of the music. Rather, the unique sounds created by the ensemble, so unique and driving on their own, flowed into one another like tributaries, bleeding together to form a whole, which constantly evolved, writhed, and drew on the diverse energies of its components. The result was nothing short of mesmerizing.

Leaving the performance, I, for the first time in a while, felt as though I had stumbled upon some sort of fundamental musical aesthetic that, if I had unknowingly been conscious of in the past, had for the longest time remained impossible to articulate. The way in which Balasubrahmaniyan and company had blended their sounds seemed elemental, as natural as the mixing of colors to create something richer. At the same time, though, the three men, the music that they played, functioned with such a respect for the depth of each part that the result seemed to transcend the mixture as well as the ingredients, reaching out past the resources that seemed available to tap into something wonderfully intricate and ethereally unified.